Know Your Chawan: A Guide to the Famous Matcha Bowl Styles

The bowl where it all happens: the chawan (茶碗 - tea bowl) is one of tea’s most iconic utensils and exists in near endless variety. As we’ve discussed in our post ‘What makes a Bowl a Chawan’, any bowl of the right size or shape can be a chawan if you use it to make tea. In fact, many of the bowls used by famous practitioners of chanoyu in Japan’s history were originally foreign rice or food bowls, but over centuries, these bowls became so popular in the tea room that today they are almost exclusively considered chawan.

Here, we’ll take a look at some of the major ‘styles’ of chawan, exploring both historical and modern examples. Many of these historical examples are meibutsu chawan (名物 - famous thing; masterpiece): famous bowls that are highly appraised by teaists through the centuries.

What defines a style?

Defining a style can be somewhat difficult as there are many overlaps and nuances that muddy the lines, never mind the fact that what defines each style is still debated. Chawan can be described in terms of shape, size, glaze, decoration, origin, clay body, etc.; with some styles being loosely defined by glaze and origin, and others being more rigid.

Most styles can be traced to collections of historical chawan and live on in modern imitations and interpretations. Modern bowls that specifically aim to imitate or replicate individual historical chawan are called utsushi (写 - copy/replica).

Outline:

- Chinese Chawan (Karamono)

- Korean Chawan (Koraimono, Korai chawan)

- Japanese Chawan (Wamono, Ima-yaki)

- Annan-yaki

Chinese Chawan (Karamono)

The earliest tea bowls that found widespread use in Japan were made in China, and were brought to Japan along with tea and tea culture in the late 1100s-early 1200s. Imported Chinese teaware, called karamono (唐物 - Tang/Chinese Items) was coveted and collected by the upper class. Due to this popularity, Japanese potters began to produce work in imitation of the Chinese styles. Sometimes these imitations are called karamono as well, referring to the style rather than the origin.

Tenmoku - 天目

By far the most famous and important of the karamono, tenmoku chawan are the most formal and revered tea bowls. Despite being known by their Japanese name, the original Tenmoku bowls came from Jianyang in Song Dynasty (960–1279) China, when Japanese monks visited the Buddhist temples of Tian Mu Mountain (天目山 - tian mu zhan in Chinese) and saw the Chinese monks making and drinking tea out of these bowls. They brought some back to Japan, calling them 天目 after the mountain where they found them. In modern Japanese, these characters are read as tenmoku, which is where we get the name.

The original tenmoku chawan are all relatively consistent in shape and size, measuring about 12cm in diameter and 7cm tall. They have a deep, conical shape with a groove around the lip, and a small foot.

Tenmoku chawan are known for their beautiful, metallic glazes, which come in three main varieties:

- Nogime (禾目- hare’s fur): the most common; streaks of blue or rust red

- Yuteki (油滴 - oil-spot): small spots against a dark backdrop

- Yōhen (曜変- glittering change): large silvery spots surrounded by iridescence

Confusingly, in addition to the original chawan and imitations of them, the term tenmoku can also refer solely to the shape of these bowls, or their various beautiful, metallic glazes.

Pictured above is the Inaba Tenmoku (稲葉天目), the most famous of the three surviving yōhen tenmoku (曜変天目) that are considered national treasures in Japan. Up until very recently, no one had been able to replicate the yōhen glaze effects. Here you can see a rare unboxing of the Fujita Tenmoku (藤田天目), one of the other two yōhen tenmoku.

Below is a modern Kyo-yaki yuteki tenmoku chawan made by Higashiyama (東山).

Seji (Celadon) - 青磁

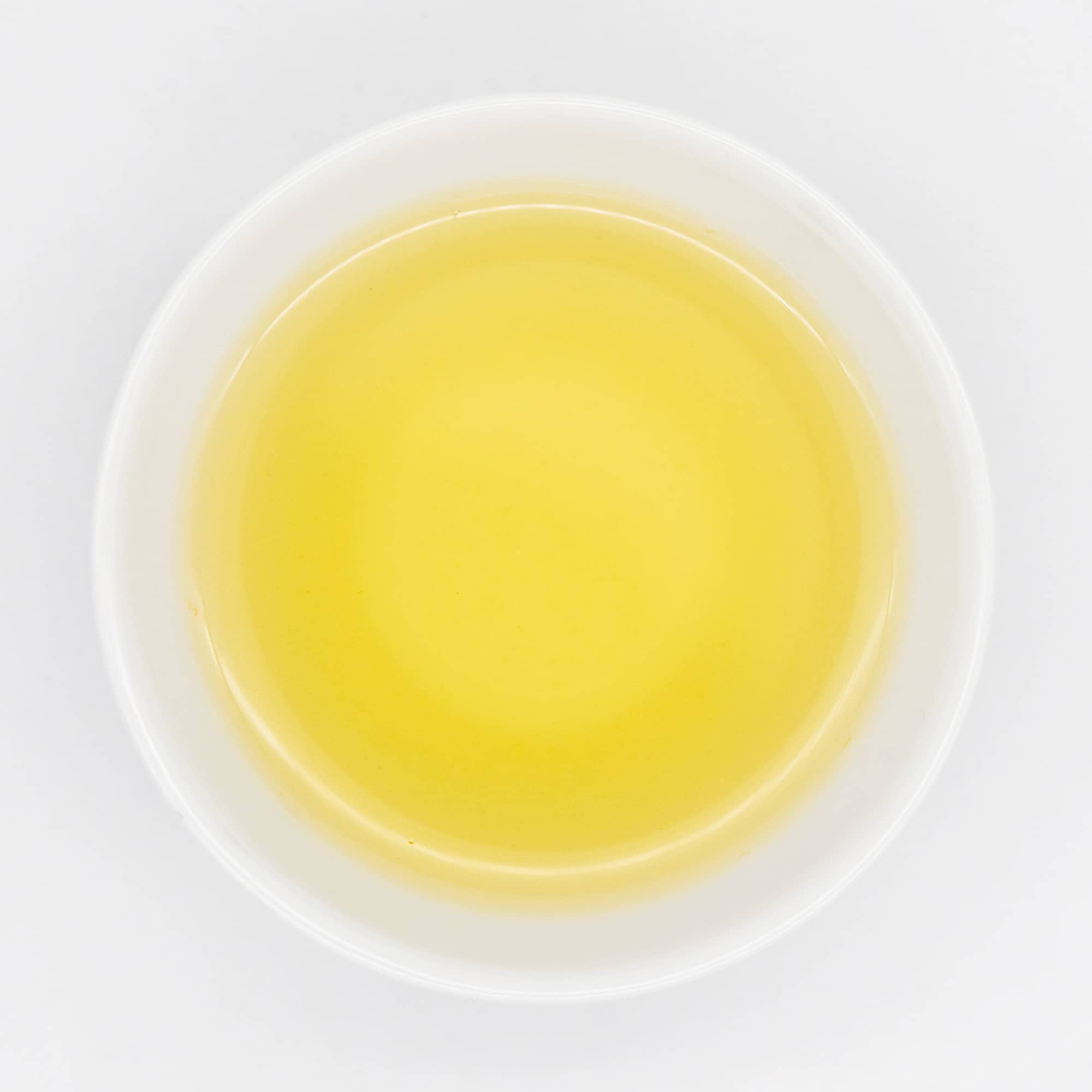

Generally speaking, celadon (also called greenware) refers to high-fired stoneware or porcelain wares glazed in a pale, translucent, crazed bluish-green. The earliest celadons were developed in the Shang Dynasty, but it was only in the Song Dynasty that celadon production became more popular, particularly from the Longquan kilns (龍泉, pronounced ryūsen in Japanese), some of which made their way into Japan.

Longquan celadon was the most highly praised in Japan, known for its simple, yet elegant shapes and beautiful blue-green hues. Compared to some other Chinese celadons, the glaze crazing is very subtle.

Later, Murata Shukō/Jukō (村田珠光) - one of the founding figures of the modern tea ceremony- expressed a preference for the cheaper, imperfect yellow-y celadon bowls, which then became known as Jukō Celadon.

For Korean celadon, see Zōganseiji (Inlaid Celadon), below.

Pictured above is Bahōukan (馬蝗絆), a national treasure in Japan and an exquisite example of Longquan celadon.

Sometsuke - 染付

Sometsuke is the general Japanese term for what is known as blue-and-white ware in English, and typically refers to porcelain wares with cobalt-blue decorations applied under the glaze. This style became popular in 13th century Jingdezhen porcelain and later spread throughout Asia. In Japan, this style is particularly popular in Arita-yaki porcelain.

While by far the most popular style in mainland China throughout the Ming Dynasty,, these wares were not popular for tea use in Japan, where the older and rarer celadons and tenmoku were preferred.

Pictured above is the Kimiidera Chawan (紀三井寺茶碗), a 15th century Ming Dynasty rice bowl used as a chawan by Sen-no-Rikyū. This may be the first ever sometsuke bowl used as a chawan.

Korean Chawan (Kōraimono)

In the same way that karamono, which means ‘Tang items’, is used to refer to all Chinese wares, kōrai is used to describe all Korean and Korean-style chawan, despite specifically referring to the Goryeo Dynasty. (It is worth noting that this is also true in English, as the word ‘Korea’ comes from ‘Goryeo’).

The vast majority of kōrai chawan are actually from the next Korean dynasty, the Joseon. These bowls first made their way into Japan in the late 15th century and gained popularity by the mid 16th century.

The styles of Korean bowls that became desirable in Japan were not ones that were considered praiseworthy in Korea, where by the 16th century, the Joseon elite were using pure white porcelain. Instead, Japan favoured the imperfect stoneware styles, some of which now fall under the category of Buncheong ware. These were the first generation of kōrai chawan to reach Japan in the late 15th century, where their loose and imperfect form was appreciated but also irreplicable, because no one in Japan had the tools, technology, or mindset required to reproduce their natural elegance.

Most of these bowls were not designed for use in chanoyu but were general rice or food bowls. The practice of adapting non-tea objects into the tea ceremony is called mitate and has long been a part of chanoyu.

Starting around the 1590s, tea masters in Japan would send designs to the Korean kilns around Busan and place orders for custom-made chawan, marking the second generation of kōrai chawan. Some of these bowls were continuations of the original styles, while others were new creations.

There is a great deal of overlap and confusion in styles between these two generations of kōrai chawan.

During the Japanese invasions of Korea in 1592 and again in 1597, Korean potters were taken hostage and brought back to Japan where they were instructed to produce Korean-style bowls on Japanese soil.

The shift in Japanese tastes from karamono to kōraimono reflects the development of wabicha. Starting with its progenitor, Murata Shukō, tea-making moved away from the elaborate, formal, ostentatious Chinese aesthetic, to a more rustic and modest aesthetic, called wabi.

Ido - 井戸

Ido chawan (井戸茶碗 - well tea bowl) are the most prized of the Kōrai chawan. The original Ido chawan were likely made around the Hadong area during the Joseon dynasty in the 15th and 16th centuries. There, they were known as maksabal (막사발), meaning ‘a bowl for everything’, and were most commonly used by peasants for rice, rice wine, or soup. As the Joseon elite preferred pure white porcelain, they considered these maksabal, and other Korean stoneware to be too cheap and coarse.

While this is the most well-known and commonly accepted story, recent research suggests that ido chawan may have originally been used for local ceremonial (non-tea) or ritual practices in Korea, thus explaining their relative rarity. If they were common food bowls, we might expect to have found more of them on Korean soil.

Either way, when these bowls made their way to Japan, their unassuming rustic simplicity and subtly uneven shapes drew the eye of teaists, and the Ido chawan became the emblematic chawan of wabicha. Ironically, these ‘cheap Korean bowls’ became some of the most expensive and sought after chawan in Japan.

There are various criteria used to judge ido chawan. While each ido chawan might not possess all of these characteristics, they are common to the style.

- Roughly conical shape

- Takenofushi koudai (竹の節高台 - bamboo node foot): a tall foot, often with a ridge like a bamboo node

- Rokurome (轆轤目 - potters' wheel marks): a subtle spiral shape left by the potter's fingers as they shaped the piece on the wheel

- Kairagi (かいらぎ/梅花皮 - plum flower texture): a crawling glaze texture on and around the foot

- Meato (目跡): unglazed spots inside the bowl where balls of clay were used to separate bowls stacked in the kiln

- Tokin (兜巾): a point at the centre of the foot

- Biwa-iro (枇杷色 - loquat colour): a rich, warm beige colour

- Sougusuri (総釉 - total glaze): the entire bowl, including the foot, is glazed

- Ō-ido (大井戸 - large Ido)

- Ko-ido (小井戸 - small Ido)

- Ao-ido (青井戸 - blue Ido)

Ō-ido bowls, like their name suggests, are very large and imposing, often over 15cm in diameter, which is actually a bit too big to be practical as a chawan (in fact, there is a famous ido bowl that Oribe thought was too big, so he broke it into pieces and reassembled it smaller). They have a tall bamboo node-shaped foot (竹の節高台 - takenofushi koudai), and a slightly curved but roughly conical shape.

Ko-ido bowls are similar, but smaller with a much less pronounced foot.

Ao-ido bowls also have shorter feet and have much straighter, conical walls without the gentle curve seen in Ō-ido bowls. The 'blue' in their name may come from the colder glaze colour that many of these bowls have.

Pictured above is the Kizaemon Ido (喜左衛門), the most famous Ido chawan (and perhaps the most famous chawan in existence) and a Japanese national treasure (Normally stored away in a temple, you can see a rare view of it here). Kizaemon is a classic example of the Ō-ido style, yet with a unique softness not seen in most other Ō-ido bowls. The rich hue of its glaze has only deepened over time and with use.

Here is a modern Japanese Kōda-yaki ido chawan. Like many modern Ido chawan, it is made in the Ō-ido shape, yet at a smaller, more practical size of only 13cm in diameter—more or less the standard chawan size. Despite their simplicity, ido chawan are some of the hardest to reproduce well, because the originals were made without any artifice or attempt at mimicking a type of beauty. Instead, their beauty is innate, formed by the potter’s hands and body rather than their mind.

Zōganseiji (Inlaid Celadon) - 象嵌青磁

The techniques to produce celadon reached Korea during the Goryeo dynasty where it took on its own distinct style. At its peak in the 12th century, Goryeo celadon was prized for its jade colour, elegant shapes, and intricate inlay patterns featuring cranes, flowers, and dragons. As the Goryeo dynasty withered, so did celadon’s quality and popularity, until production eventually ceased in the early Joseon dynasty.

Compared to Longquan celadon, Goryeo celadon typically had a greener hue, elaborate designs, and was usually made from stoneware rather than porcelain.

As the aesthetics of wabi became more popular, Japanese tastes moved away from fancy Chinese teaware and towards simplicity and imperfection. As such, the elaborate designs of Korean inlaid celadon rarely found use in the tea room. The inlaid celadon that did get used typically came from the tail end of the Goryeo or the beginning of the Joseon dynasty, and was of lower quality, thus suiting Japanese tastes.

One such bowl is Rikyū’s Hikigi no Saya (引木の鞘), pictured above. As you can see, the colour is more grey than green, and the inlay work is somewhat sloppy. These imperfections are favourable in the aesthetics of wabicha.

Here is a 20th century Korean chawan that replicates Korean celadon at its peak. Notice the more vibrant hue and sharper inlay work. The crane and cloud motif is called unkaku (雲鶴) and was very common, so much so that Korean inlaid celadon bowls are sometimes called unkaku chawan.

Gohonte - 御本手

Gohonte is less a style of chawan and more of a glaze effect. It typically refers to an array of pink or white spots against a grey or beige background, often made when a piece coated with white slip and covered in a transparent glaze is fired in reduction. It gets its name from the order forms and catalogue books (御本 - gohon) that tea masters used in the Azuchi-Momoyama period to order tea bowls from potters and kilns in Korea. Many of those gohon chawan (御本茶碗) had these spots, hence the name gohonte. They often appear on many other kōrai chawan styles, especially kohiki and totoya chawan.

Today, gohonte is especially common in Hagi-yaki and can also be seen in Asahi-yaki, where it is also called kase (鹿背 - deer’s back) due to its resemblance to the spots on the back of a deer.

Pictured above is a Korean e-gohon chawan (絵御本茶碗 - painted gohon tea bowl) from the Joseon dynasty. Below is a modern Hagi-yaki chawan with a pronounced gohonte pattern.

Mishima - 三島

In modern usage, mishima refers to a decorative technique called slip-inlay developed in Korea around the 15th century. Much like with inlaid celadon, designs would be carved, etched, or stamped into the clay. However, instead of being carefully filled with coloured clay, the entire piece is coated in white slip (liquid clay), and the excess is then scraped off, leaving just the designs filled with white slip. Finally, the piece is finished with a transparent ash glaze.

Common designs are incised lines, geometric patterns, and stamped flowers (印花 - inka), often sakura or chrysanthemums.

The earliest mishima chawan are called ko-mishima (古三島 - old mishima) and belonged to the first generation of kōrai chawan. However, the vast majority of Korean mishima chawan were produced as gohon chawan (御本茶碗) in the late 1500s and throughout the 1600s. The mishima technique was often combined with other slipware techniques such as hakeme and kohiki (see below).

Pictured above is Rikyū’s personal mishima chawan, the mishimaoke (三島桶), and is likely an example of ko-mishima. Its cylindrical shape is atypical of the mishima style, and lends it the oke (桶 - bucket) part of its name.

Here is a modern Kyo-yaki mishima chawan made by Yohei Nakamura (中村与平).

Hakeme - 刷毛目

Like mishima, hakeme is a slip decoration technique. Here, white slip is applied with a brush, originally across the majority of the piece, but later more as an accent. On top of this layer of slip, the bowl is finished in a transparent ash glaze. The hakeme technique was especially common on earlier Buncheong vases, often being used as a base for further decoration. Called gwiyal in Korean, hakeme typically employs a very coarse bristled brush, so that the resulting strokes are rough with a lot of character. When the slip is brushed across the entire piece, except for the foot, it is called mujihakeme (無地刷毛目). These bowls tend to be plain white and can be confused with kohiki chawan.

The original hakeme chawan likely belong to that first generation of kōrai chawan, but like mishima bowls, many were later designed and ordered by Japanese teaists.

Pictured above is a 16th century Korean hakeme chawan. Hakeme is very commonly combined with mishima as can be seen on this modern chawan by Kengo Sugawara:

Kohiki - 粉引

Kohiki is another traditional Korean slipware technique that originated in the short-lived Buncheong ceramics of late 15th century Korea. In an attempt to create an affordable mimicry of the prestigious Baekja white porcelain used by the Joseon elite, iron-rich clay was entirely (foot included) dipped in white slip (liquified clay) and again finished with a translucent ash glaze. When being dipped, the bowls are held by the foot using three fingers, usually leaving three unglazed spots around the foot called yubi-ato (指跡 - finger prints). The practice of glazing the entire bowl is called sougusuri (総釉 - total glaze). This sets kohiki chawan apart from the aforementioned mujihakeme chawan.

In Korean, this slip-dipping technique is called deombeongi. Compared to the harsh white of porcelain, kohiki vessels have a soft, warm, and organic white. The Japanese term kohiki means ‘powdery’, alluding to this soft white finish.

Because the ash glaze never touches the clay body (as the slip covers the entire piece) it cannot bond with the clay, resulting in a weak and porous finish. This porous nature of kohiki ware means that over time, it will develop a deep, rich patina as tea seeps its way into the glaze. As such, they are seen as 'breathing vessels' that age and develop alongside their owners.

Additionally, depending on the glaze, slip, clay body, firing schedule, etc., some kohiki chawan are so porous that the glaze readily absorbs water, as can be seen here, resulting in small water spots, called amamori (雨漏り - rain leak). These will usually disappear as the chawan dries. Over time, however, they can become permanently stained with tea, producing a beautiful effect.

This glaze staining can be seen in the famous 16th century Korean Miyoshi Kohiki Chawan (三好粉引茶碗 ) shown above. This chawan was at one point personally owned by Toyotomi Hideyoshi. Miyoshi also presents a great example of a common decoration on kohiki bowls, the hima (火間 - fire space): a narrow wedge that is intentionally left uncovered by slip, showing the bare clay underneath. Typically there is also a drop of slip running across the hima, also present on Miyoshi. Both the hima and this drop of slip across it may have originally been accidents, but by the time Miyoshi was made, they were intentional decorations and can be seen on the other famous kohiki chawan from this era.

Here is a modern Kyo-yaki kohiki chawan in a flat, summer style made by Yohei Nakamura (中村与平). When it was new, Miyoshi was also a similar shade of white. Over time and with use, this chawan will also develop a patina. Areas where the slip is thin or missing, such as the hima or the three finger spots around the foot, also turn black if the clay has a high enough iron content.

Outside of chawan, kohiki is seeing a resurgence in everyday tableware, as the soft white presents a rustic yet timeless alternative to porcelain. Here you can find our ever-growing collection of kohiki wares.

You can see the process of making modern Korean and Japanese kohiki chawan here.

Irabo - 伊羅保

Irabo chawan firmly belong to the second generation of kōrai chawan, made specifically for use in chanoyu. As such they reflect Japanese aesthetics more than Korean aesthetics. Consisting of a thin iron-rich earth ash glaze over a coarse, stony, iron-rich clay body, irabo chawan are prized for their rough finish and irregular ochre-coloured glaze.

Variations on the irabo style are ki-irabo (黄伊羅保 - yellow irabo), yellow-y bowls fired in oxidation; and kugibori-irabo (釘彫り伊羅保 - nail carved irabo), which have gouged spirals that look as if they were carved by a nail.

Pictured above is an original kugibori-irabo chawan called Kokeshimizu (苔清水), which has an exceptionally pronounced ‘nail gouge’.

Below is a modern Kiyomizu-yaki irabo chawan:

Goshomaru - 御所丸

One of the lesser-known and more intriguing styles of kōrai chawan, goshomaru bowls get their name from trading ships (maru is a common Japanese ship title) that ferried goods between Japan and Korea.

Of the 664 documented kōrai chawan in Japanese museum and private collections, only 17 are goshomaru chawan. This small number traces them back to one kiln in the Gimhae region, and perhaps even one individual potter. These 17 bowls can be further split into two categories:

- Honte/Hakute (本手/白手): plain white glaze

- Kurohake (黒刷毛): white glaze accented with black brush strokes

12 of the 17 goshomaru bowls are honte, while the other 5 are kurohake. Research points to the honte style being the original, with kurohake being a later development.

Both types share the same major features:

- Kutsu-gata (沓形 - clog-shaped): a heavily distorted shape where the sides of the bowl have been warped inwards, making it more oblong or lopsided than round

- Polygonal foot: the foot ring is shaved and cut into a pentagon, hexagon, or octagon

- Dense, almost porcelain-like high-fired stoneware body

- White glaze that does not cover the foot

Their intentionally distorted shape and polygonal foot are unique features among kōrai chawan, and likely point to a Japanese origin for their design, meaning that the goshomaru bowls are gohon chawan (御本茶碗) ordered by Japanese teaists as part of the second generation of kōrai chawan.

Pictured above is the most famous of the kurohake goshomaru chawan: Yūhi (夕陽 - sunset). A rare unboxing of this chawan can be seen here (Japanese only).

Not only are these bowls markedly different to other kōrai chawan, they bare more than a passing resemblance to kuro-oribe chawan (see below). Though the exact details are debated, there can be no doubt that these two styles are related. There are two potential explanations:

- Goshomaru bowls came first, potentially ordered by Oribe himself, and were a prototype/inspiration for the kuro-oribe and oribe-guro styles

- Kuro-oribe bowls came first, establishing the oribe gonomi style of distortion and abstract decoration. Goshomaru bowls were then designed and ordered by Japanese patrons who wanted bowls in this style.

A more thorough exploration of their relationship can be read in Annegret Bergmann’s research paper.

Japanese Chawan

Wamono - (和物)

For the early period of chanoyu’s history, domestically produced Japanese wares were considered too lowly to be used in the tea room, as Japanese ceramic technology was far behind that of China and Korea (and also because restricting tea to using only expensive foreign wares allowed the rich elite to exert more control). This first began to change with Murata Shukō/Jukō (村田珠光) in the late 1400s, when he used unglazed Japanese vases in the tea room as part of his wabicha. This new style of tea ceremony reach its zenith with Sen-no-Rikyū (千利休) who finally popularised the use of domestic chawan when he developed the Raku chawan. His student and successor as the leading tea figure in Japan, Furuta Oribe (古田織部), continued the development popularisation of Japanese-made chawan, establishing a unique and truly Japanese ceramic style and aesthetic, distinct from the Chinese and Korean styles that came before it.

The wa in wamono technically means ‘harmony’, but is used in many words to reference Japan, such as wagashi (和菓子 - Japanese sweets) and washoku (和食 - Japanese food). These wares are also sometimes called koku-yaki (国焼 - country/domestic wares) or ima-yaki (今焼 - now/contemporary wares). Though ima-yaki was a popular term when these styles were being developed, it no longer makes much sense.

Because wamono chawan originated in Japan, the styles are much more closely linked to the regions and kilns where they were developed, and as such are often sorted by region.

Seto - 瀬戸 / Mino - 美濃

Seto-yaki was among the most technologically advanced of the Japanese ceramic regions, producing the first glazed wares in Japan, often mimicking continental pieces. Some of the oldest chawan made in Japan were Seto-yaki replicas of Tenmoku and celadon wares. These early Seto-yaki pieces are called ko-seto (古瀬戸 - old Seto). As Seto ceramic production spread to Mino in the 1500s, new ceramic styles were born. These styles generally fall under both the Mino-yaki and Seto-yaki categories. While today Mino-yaki and Seto-yaki are considered separate styles today, it seems that during the 15-1600s, there was no distinction.

Ki-Seto - 黄色瀬戸

Literally translating to yellow Seto, ki-Seto is a glazing style where an ash-based glaze turns yellow in oxidative firing. Originally used on tableware, it was also applied to chawan for use in the tearoom.

Ki-seto chawan generally came in two shapes: wan-nari (椀形 - wooden bowl-shape) and hantsutsu-gata (半筒型 - half cylindrical type). Decoration, if present, was simple, usually inscribed lines or flowers. The main draws were the various subtle glaze effects:

- Aburaage-de (油揚手 - deep-fried tofu style): a thick, matte yellow with a slightly textured surface, similar to that of deep-fried tofu pouches

- Tanpan (胆礬 - chalcanthite): splashes of green glaze, ideally naturalistic. Cheaper modern Ki-seto wares often have very artificial looking tanpan. This green comes from copper sulphate.

- Koge (焦げ - scorch marks) areas where the glaze has turned brown as if scorched

Pictured above is Nanba (難波 - Difficult Wave), which likely wasn’t made as a chawan, but was ‘mitate-d’ into the tea room. It possesses all three of the above mentioned glaze effects, and shows the minimal inscribed decorations. It seems bowls of this style were produced in large quantities, but Nanba is the most famous. In addition to having many utsushi (写 - replicas), it also serves as inspiration for many modern Ki-seto bowls, such as this one by Noda Higashiyama (野田東山):

Shino - 志野

Shino represented a step forward in Japanese ceramics, being the first white glaze developed there, sometime in the mid 1500s. Made from feldspar mixed with some clay, this glaze produced milky white colour with a surface that is occasionally textured with pinholes, called 'suana' (nest holes) or 'yuzuhada' (ゆず肌 - yuzu skin) in Japanese. Shino chawan were typically hantsutsu-gata (半筒型 - half cylindrical type), which became the popular style for Japanese chawan during the Momoyama era. These are not perfect half-cylinders, however, as the hand-powered pottery wheels of the time did not spin fast enough to produce perfectly round wares. In China and Korea, kick wheels were used to produce more symmetrical bowls, but this technology had yet to make it to Japan.

Undecorated white shino is called mujishino (無地志野) where the main attractions are the glaze’s natural colour variations and the orange-brown hiiro (火色 - fire colour/marks). This white glaze served as a sort of blank canvas, allowing potters to paint designs using iron glaze in a sub-style called e-shino (絵志野 - painted shino). In addition to white, the glaze could also be made in red as beni-shino (紅志野 - red shino) or a greyish-blue called nezumi-shino (鼠志野 - mouse-coloured shino) or haiiro-shino (灰色志野 - ash-coloured shino).

Pictured above is Hirosawa (広沢), an original mujishino chawan displaying a beautiful combination of white and hiiro. You can see an unboxing of this bowl here.

Below is a modern nezumi shino chawan made by Katou Hideyama (加藤秀山):

Seto-guro - 瀬戸黒

Developed in the late 1500s by Mino potters, potentially at the direction of Furuta Oribe (古田織部), Seto-guro (瀬戸黒 - Seto Black) bowls have a tall cylindrical or half-cylindrical shape and a glossy black glaze. This glaze has a high-iron content, around 10%, and the black colour comes from the hikidashi-kuro (引き出し黒 - pull-out black) technique in which the piece is removed from the kiln while still red hot, around 1,200°C. The rapid cooling turns the iron glaze black. For even more rapid cooling, sometimes the bowls would be quenched in water. The faster cooling gives these bowls a glossier finish. Glazes also contract as they cool, so the rapid temperature shock causes crazing (small crackles in the glaze). To remove a bowl from the kiln while the kiln is still being fired, tongs are inserted through the small windows through which the firing is observed. As only a few bowls can be reached from these windows, very few setoguro chawan can be made from a single firing.

The hikidashi-guro technique is also used to make kuro-raku chawan (see below) and it is likely that setoguro bowls were developed first. Seeing as Rikyū owned and used several setoguro chawan, they may have been an inspiration.

Like shino chawan, setoguro bowls have imperfect shapes with visible tooling marks. Many also have a yamamichi (山見 - mountain path) style undulating lip along with an incredibly short foot.

Pictured above is Oharagi (小原木) which is said to have been loved by Rikyū. You can see an unboxing of it, along with a demonstration of hikidashi-guro here.

Oribe - 織部

The three main Oribe styles belong to the same Seto/Mino tradition as the previous group. They get their name from influential and revolutionary chajin Furuta Oribe (古田織部), who was a student of Rikyū and succeeded him as being the leading aesthete and teaist in Japan. The extent of Oribe’s personal involvement with the ceramic styles that bear his name is debated. At the bare minimum, Oribe placed orders for distorted tea bowls from Mino (his hometown). At most, he personally designed or even helped make Shino, Setoguro, and Oribe chawan (which I find to be more likely). Either way, his influence had a profound effect on the shape (literally) of Japanese ceramic arts.

While those who came before him, such as Rikyū, Jōō, and Shukō pioneered the wabi aesthetic, praising the natural imperfection, humility, simplicity, and lack of artifice found in Korean bowls (and later in Raku chawan, in Rikyūs’s case), Oribe took this a step further: instead of natural imperfections, Oribe purposely distorted his bowls, manipulating them into various warped shapes. On top of this, he painted abstract or childish designs. This played into his aesthetic philosophy, called hyouge (ひょうげ/剽げ/へうげ) which roughly translates to ‘playful’, ‘charming’, ‘jocular’, etc.

Oribe-guro - 織部黒

Oribe-guro (織部黒 - Oribe black) can be seen as an evolution of seto-guro. Keeping the low foot and hikidashi-guro glaze, Oribe exaggerated the natural distortions and undulating lip, forming what is known as kutsu-gata (沓形 - clog-shaped). Kutsu-gata usually comes in two forms: squishing two opposite sides so that the bowl is oblong, or squishing three sides so that the bowl vaguely resembles a tricorn hat. This warped shape is common to most Oribe chawan.

Oribe-guro introduced another feature common to most Oribe chawan: the folded lip. Here, the lip of the bowl is folded outward on itself, so that it is double thickness around the top of the bowl.

The bowl picture above is known as Ichimonji (一文字 - “1” Character) as the space between the folded lip and the bottom of the bowl make a horizontal line, evoking the kanji 一 meaning “1”.

Kuro-Oribe - 黒織部

Kuro-Oribe (黒織部 - Black Oribe) is yet a further evolution of the style, combining the warped shape and hikidashi-guro glaze of Oribe-guro bowls with the white glaze and abstract iron painting of e-Shino ware.

The white glazed sections contain the painted designs and are bordered and framed by the glossy black glaze

These bowls bear a striking resemblance to goshomaru chawan (see above) and are certainly related. However, kuro-oribe bowls tended to be a tad larger and made from less dense and coarser clay. While a few of the kurohake goshomaru bowls have similar abstract designs, goshinaru bowls are generally more naturalistic and flowing in their decorations.

Although ao-Oribe is the most popular style today, kuro-Oribe chawan actually make up the majority of the famous Oribe bowls from the late Sengoku and early Edo periods.

Pictured above is Waraya (わらや), made either in the late 1500s or early 1600s. It has a low, wide shape and an extremely distorted lip.

Here is a modern Kuro-Oribe bowl by Hiroshige Katō, inspired by Waraya.

Ao-Oribe - 青織部

The final development of Oribe ware, Ao-Oribe (青織部 - Green Oribe) replaces the hikidashi-guro glaze of kuro-Oribe with a copper based green enamel. Though originally used for chawan, this style was also applied to tableware where it became incredibly popular and is now the most stereotypical and recognisable type or Oribe-yaki.

Pictured above is Yamaji (山路), which includes a red glaze underneath the painting for further contrast and interest.

Here is a modern example by Mino potter Katō Tatsutō (加藤辰陶).

Raku - 楽

Raku-yaki (楽焼) or Raku ware is perhaps the most iconic style of wamono chawan. Though it may not have been the first wamono style to be developed, it was the first to gain widespread acceptance. This was because Raku chawan were developed and promoted by the most influential tea master of all time, Sen-no-Rikyū (千利休), sometime in the late 16th century.

Perhaps inspired by the recently created hikidashi-guro (引き出し黒) technique used to produce the Seto-guro style of black chawan, Rikyū collaborated with tile-maker Chōjirō (長次郎), using this technique to produce bowls that captured the essence of his style of wabicha, a bowl that exuded simplicity and imperfection.

Hand-formed from porous clay rather than wheel-thrown, raku chawan are then bisque-fired, glazed, and then fired individually or in small batches for a short amount of time at relatively low temperatures before finally being removed from the kiln while still glowing hot. The resulting bowls are very light and porous - imperfect in both shape and construction. Unlike porcelain or high-fired stoneware bowls which produce a high-pitched, bell-like ring when tapped, raku bowls are so low-fired that they only produce a dull thud.

The vast majority of raku chawan are made in the hantsutsu-gata shape, and are generally circular, with naturalistic imperfections, rather than the intentional distortions that Oribe would apply to his bowls.

Compared to seto-guro chawan, raku bowls generally have a softer shape with a lip that curls inwards slightly.

Originally, raku chawan were always undecorated, as, in Rikyu’s eyes, decoration is an unnecessary artifice that distracts from the pure elegance of raku bowls’ simplicity. Today, however, it is not uncommon to find painted or otherwise decorated raku chawan.

When first made, these bowls may have been called Juraku-yaki (聚楽焼) as they were fired on the grounds of Hideyoshi’s Jurakudai palace (聚楽第). Hideyoshi gave both the wares the seal of ‘Raku’ (楽) meaning ‘enjoyment, and gave this name to Chōjirō himself as well. The descendants of Chōjirō continue to bear the family name Raku and still produce raku chawan to this day.

It is worth noting that ‘raku’ in the realm of western ceramics arts, refers to a derivative, but separate practice.

Kuro-Raku - 黒楽

The earliest and most famous raku chawan are known as a kuro-raku (黒楽 - black raku) and as their name suggests, have a plain black glaze. This glaze was originally made from a mixture of white lead and stones from the Kamogawa river, though modern formulations vary. These bowls are generally fired individually at temperatures around 1000-1200°C for 1-2 hours before being removed with tongs and either cooled by air or with water. Depending on the glaze formulation, firing temperature, and cooling method, the lustre can range from very glossy to a dull matte, with higher temperatures and faster cooling leading to glossier finishes.

Pictured above is Omokage (面影) one of Chōjirō’s original kuro-raku chawan. Compared to his other black raku bowls, Omokage has a rougher, duller finish, with a lot of texture and colour variation. You can see a rare unboxing of it here.

Here is a modern chawan by Shunpo Heian (平安春峰), with a glossier glaze, more angular shape, and visible tong marks.

Aka-Raku - 赤楽

The second most popular style of raku chawan is aka-raku (赤楽 - red raku). These are traditionally glazed in a transparent lead-based glaze (though modern formulations vary and lead-free recipes exist), before being fired at a lower temperature of around 700-900°C and allowed to cool slowly. The colour of aka-raku bowls can vary from a vibrant red, with white and black colour variations, to a more muted orange or pink.

Above is another of Chōjirō’s original raku chawan, Tarōbō (太郎坊) which you can see in a rare unboxing here. It sports a more muted glaze, tending towards shades of brown and umber.

Here is a modern aka-raku chawan named Kōjitsu (好日 - Good Day) by Sasaki Shoraku (佐々木松楽) of Shoraku Kiln (松楽窯). This bowl has a much more vibrant red glaze, a pronounced waist, and a more varied appearance, with patches of black accenting the red.

Ame-Raku - 飴楽

Ame-raku (飴楽 - candy raku) is found primarily in Ohi-yaki (大樋焼). Located in Kanazawa, Ishikawa Prefecture, it is an offshoot of traditional raku-ware, with the first Ohi potter being the son of Raku III and apprentice to Raku IV. The first Ohi kiln was opened in 1666, and for six generations made tea ware exclusively for the Maeda Clan, but since the 7th generation in the mid-to-late 19th century, began producing tea ware and other ceramics for the general public.

The ‘candy’ part of the name refers to the type of glaze, called ame-yu (飴釉 - candy glaze). This is a high-iron glaze known for its delightful variations and unevenness in colour and texture, getting its name from its overall caramel colour. Early examples of this glaze style date back to the Kamakura period. It can range in colour from a deep, burnt brown, to a vibrant orange.

Above is by Tachimine (立峯) by Hon'ami Kōetsu (本阿弥光悦). Koetsu was one of Oribe’s pupils and was gifted clay by Chōjirō’s grandson, becoming one of the greatest Raku potters, developing his own unique style, distinct to that of the Raku family. Tachimine has a low, almost invisible foot; a soft, rounded shape; and a deep ame-yu glaze.

Pictured here is a modern example by Izumi Kisen III (泉喜仙) a third generation potter at the Shoun Kiln (松雲窯) and one of the few female chawan potters. As far as ame-raku bowls go, this glaze is on the darker side.

Hagi - 萩

Hagi-yaki (萩焼), or Hagi ware, is a regional style of Japanese ceramics that comes from the area around the town of Hagi in Yamaguchi Prefecture. Hagi-yaki has its origins in Japan’s invasions of the Korean Peninsula in 1592 and again in 1597, led by Toyotomi Hideyoshi. Though ultimately unsuccessful, this campaign, sometimes called the Imjin War, devastated Joseon Korea, who eventually repelled Hideyoshi’s forces with the help of Ming China. During their occupation, Japan relocated thousands of Korean scholars and craftsmen to Kyushu in Southern Japan. Many of the potters that were brought to Japan began to build new kilns, creating what are now some of Japan’s most well-known regional styles, such as Arita-yaki, Agano-yaki, and Karatsu-yaki.

Among these potters were the brothers Ri Shakko and Ri Kei (likely the Japanese forms of the Korean names Yi Sukkwang and Yi Kyung respectively), who were brought to Japan by the warlord Mori Terumoto of Hagi. There they set up their first kiln with his patronage and fired the first piece of Hagi ware around 1604. At first, Hagi ware produced chawan similar to the Kōrai styles these Korean potters were used to—such as ido and gohonte—but eventually new styles were developed, though most retained a Korean ‘spirit’. As half-cylindrical chawan were favoured by the mid 1500s and early 1600s, Hagi potters quickly began making chawan in this shape, in addition to the more classical Korean shapes.

Like many kōrai chawan, Hagi teaware is also said to improve with age over the course of decades and even centuries. As tea slowly stains the clay through the fine cracks in the glaze, it deepens and enriches the piece’s colour and texture in a process known as nanabake, or "the seven transformations". This ability to capture the passage of time only adds to its allure. Although, interestingly enough, the exact definition of each of the "seven" transformations is disputed by many experts in the field.

After the Meiji Restoration and the end of Mori clan patronage, Hagi ware saw a lapse in popularity before it was revived by the work of Miwa Kyuwa and the resurging interest in traditional arts in the Taisho and early Showa Eras. Today it is one of Japan’s most popular and recognisable ceramic traditions and enjoys tremendous popularity.

Pictured above is an early Edo-era Hagi-yaki chawan, made in the hantsutsu-gata shape.

Here is a modern Ido-style Hagi chawan made by Ken Komatsu (小松健):

Oni-Hagi - 鬼萩

One of Hagi-yaki’s distinctive newer styles is Oni-Hagi (鬼萩 - demon hagi), created by Miwa Jusetsu (Kyusetsu XI) sometime in the 1980s. The Miwa family is one of the oldest families of Hagi potters, descending from Miwa Kyusetsu who founded the Matsumoto Kiln in 1663. Inspired by the power of the rough sea, Jusetsu crafted strong and striking forms from a coarse clay made by mixing large amounts of sand into daido clay. He first brushed these pieces with an iron rich glaze, then dipped into the shira Hagi straw ash glaze, twisting the pieces as the glaze dried so that it would drip and flow in interesting ways. After firing, the areas brushed with the iron rich glaze turn a deep black, providing a stark contrast against the bright white of the straw ash glaze. The overall impression is one of deep texture, power, and contrast.

Shown above is one of Miwa’s original Oni-hagi chawan.

Karatsu - 唐津

Karatsu-yaki (唐津焼) is another ceramic tradition founded in the 1600s by captured Korean potters. As with Hagi-yaki, the early bowls produced at Karatsu were continuations of kōrai styles, and the new styles that later developed continued to have a more ‘Korean’ feel.

There are many Karatsu-yaki substyles, with the most popular perhaps being e-karatsu and chosen-karatsu.

E-Karatsu - 絵唐津

E-karatsu (絵唐津 - painted Karatsu) use an iron underglaze to paint simple decorations, which is then covered in a transparent or semi-transparent ash glazed. This style has a rustic elegance, with the transparent glaze showing off the rich, earthy tones of Karatsu’s clay.

Above is the most famous example of an original e-karatsu chawan, decorated with a stark yet simple painting of a Japanese iris (アヤメ - ayame).

Below is a modern bowl by Yū Ōhashi (大橋裕) of Ōsugisaraya Kiln (大杉皿屋窯) decorated with a chidori (千鳥 - thousand bird/plover) motif:

Chosen-Karatsu - 朝鮮唐津

The significance and origin of the name chosen-karatsu (朝鮮唐津 - Joseon/Korean Karatsu) are not well understood. This style employs two glazes: a white glaze made from straw ash and an iron-rich black glaze. These glazes are layered so that as they melt in the kiln, they run into each other and mix in chaotic and beautiful patterns.

Above is an early example while below is a modern piece.

Iro-E Kyō-yaki - 色絵京焼

There are many styles of chawan produced in the Kyōto area and few are as synonymous with the term Kyō-yaki (京焼 - Kyōto wares) as the colourful overglaze painted styles. While there is no agreed upon term for the general Kyōto style, the term iro-e ( 色絵 - colourful paintings) refers to the technique of overglaze painting. Unlike the painted styles detailed above which used iron pigments applied underneath a transparent glaze, overglaze decoration uses enamels applied on top of the glaze. This allows for much more colourful and detailed designs and images. The development of this style can be traced to three individual potters. Nonomura Ninsei (野々村仁清) and his student Ogata Kenzan (尾形 乾山) pioneered the style in the early-mid Edo period. Later in the 1700s, Okuda Eisen (奥田頴川) introduced porcelain technology to Kyōto which made overglaze painting easier.

Ninsei's style was so varied, I have included two examples here. Above is a more subdued bowl with a subtle and restrained painting of a narcissus. Below is his much louder and more abstract ‘scale-wave’ bowl, which has abstract, geometric scales painted in overglaze, covered with a large, dripping patch of blue glaze.

Both of these bowls have the same shape which is common to iro-e Kyo-yaki, and yet lacks a proper name. A variation on the classic wan-nari (椀形 - wooden bowl shape) style, there is an ever so slight waist or tightening of the torso, accompanied with a slightly inward facing lip.

This same shape can be seen on this modern bowl by Eikō Miyaji (宮地英香), which has a beautiful fuji (藤 - wisteria) decoration.

Annan - 安南

In addition to China and Korea, Japan also imported bowls from other Asian countries. These are collectively known as shimamono (島物 - island wares) as they were believed to have come from various island nations. One of the most popular shimamono styles is annan-yaki (安南焼 - Annam ware) which refers to Vietnamese painted porcelain (Vietnam was also called ‘Annam’ in Europe for some time).

As mentioned above, sometsuke or Chinese blue-and-white painted porcelain spread throughout Asia. It reached Vietnam sometime between 1200 and 1400, where it developed into a unique local style. Compared to the bright white of Chinese porcelain, Vietnamese porcelain had a softer tone. The blue painting was also softer, with looser brush work and a less vibrant pigment. The shapes of annan bowls were also unique with a tall, wide foot and flaring lip.

Above is an original Vietnamese chawan and below is a modern Japanese replica:

While there are many other chawan styles, these are some of the most common and most famous types. To learn more about chawan, check out our blogs on their shapes and what features set chawan apart from other bowls.